By Rebecca Duncan, author of South African Gothic: Anxiety and Creative Dissent in the Post-apartheid Imagination and Beyond.

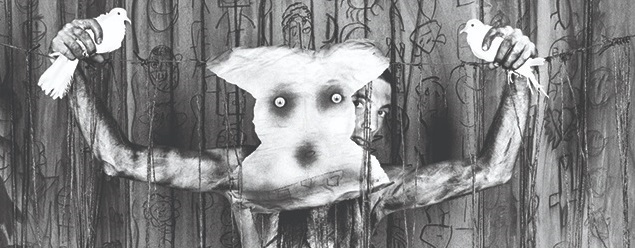

Emerging in the shadow of eighteenth-century Enlightenment, as the first shudders of industrialising change were becoming palpable in Britain, Gothic fictions have, over the two hundred and fifty years since the mode’s genesis, tended to proliferate at moments of upheaval or transformation. Gothic is always in some sense what David Punter calls the ‘literature of terror’ (1996). It is populated by strange, violent and sometimes fantastically realised figures of dread, at the kernel of which lie very real anxieties. Gothic narratives register material fears simmering in the socio-economic, political and cultural contexts in which they are produced, fears that multiply and intensify at those bewildering, disorientating historical junctures (of which the industrial revolution is one example) where established patterns of life are disrupted as these give way to, and partially overlap with, a new, strange configuration.

The fall of the institution that, over the twentieth century, became known as South Africa’s apartheid state constitutes one such moment of change. The country’s first free and fair election in 1994 was to birth (at least at the level of national rhetoric) what Archbishop Desmond Tutu would indelibly designate the ‘rainbow people’: a unified but culturally diverse South Africa, characterised by equality, respect and tolerance, and which was thus sharply different from the country of the past. And yet, the sense of jubilation that accompanied the dawn of this ‘new’ South Africa emerges alongside more difficult and less euphoric processes and phenomena, which serve to complicate triumphal narratives of liberation from history. Between 1996 and 1998, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) publicly heard testimony from victims and perpetrators of apartheid-era human rights violations, and in so doing exposed the scale and intensity of what that tribunal was itself designed to lay to rest. Over the post-apartheid period more widely, the rainbow has been called profoundly into question by crime, xenophobic and gendered violence, state corruption, and police brutality – all of which can be related in some sense to economic neoliberalisation. Underway in South Africa since the dawn of democracy, the effect of the post-apartheid neoliberal turn has been to preserve – and not to eliminate – conditions of racialised inequality, so that in a very real sense South Africa’s past is not past at all, but a matter of daily experience.

Amid these fraught conditions, where the loaded relation between past and present becomes complex, and rainbow-tinted expectations are betrayed, a gothic current becomes discernible in South African literary writing. Or rather, it becomes increasingly discernible, since Gothic has, in different ways, been a feature of South African literature at least since the late nineteenth century, which was itself a period of upheaval, when the discovery of diamonds and gold kick-started South Africa’s ‘mineral revolution’: those processes of rapid, mining-driven industrialisation, engaged in gothic terms by such colonial writers as H. Rider Haggard and John Buchan.

Around a century later, when a different kind of revolution seemed increasingly likely, gothic forms again begin to appear with particular frequency in South African writing, and it is chiefly (but not exclusively) with these that South African Gothic is concerned. After engaging briefly with gothic impulses in colonial-era and early twentieth century writing from South Africa, discussion in the book turns to the late-apartheid period dubbed the ‘interregnum’ by Nadine Gordimer – that time when, to paraphrase her own adaptation of comments from Antonio Gramsci, white supremacy’s death knell was sounding in South Africa. But it remained as yet anxiously unclear what kind of politics would take its place (1988: 263). In the context of this climate, in a South Africa where the future drops out of sight, I explore a spate of gothicised farm narratives, written during the last two decades of official apartheid, in which the deeply conservative genre of ‘white pastoral’ literature is self-consciously invoked (Coetzee, 1988), only to be invaded – made to warp and distort – by gothic figurations of a history of institutionalised violence.

Discussion then turns to the transition to democracy: to the time of the TRC, of excavating obscured truths and shedding light on the past. What is to be made, the book asks here, of the peculiarly authentically gothic hauntings that recur in the writing of this period, especially if early gothic fictions are in some sense – as Fred Botting puts it – ‘attempts to explain what the Enlightenment left unexplained’ (1996: 23)? And if gothic operates in this way outside an Enlightened language of stable truths, then what kind of history is it that gothic writes in the transitional South African context? Might a wilfully obscure gothic account help to resist forgetting as it refuses closure, so that – rather than remembering fully – it mourns what has gone before?

In the book’s penultimate chapter, discussion turns to the recent proliferation of horror narratives in post-millennial South Africa, which – as they demonstrate a preoccupation with the bodily vulnerability – share in and dramatise real concerns circulating within the post-apartheid nation. These find esoteric expression, anthropologists Jean and John L. Comaroff note, as a fear that evil-doers are abroad, harvesting human organs for use in magical ritual or transforming ordinary people into zombie labourers to be exploited for ill-gotten personal gain (1999). What is the connection, this chapter asks, between such occult beliefs and practices and the literary renditions of body horror with which they are contemporaneous? And in what sense might both be viewed as responsive to the strange circumstances, in which rhetorics of post-apartheid liberation circulate with high visibility amid deeply precarious conditions of still-racialised poverty and privation?

Gerald Gaylard identifies a suspicion surrounding the sign ‘gothic’ within South African literary criticism of the apartheid period in particular. In these circles, and as a term for categorising literary texts, ‘gothic’ has appeared frivolous and fantastical, and as such ill-equipped to bring into focus the ‘political or committed’ dimensions of fiction written in the context of very real political oppression (2008: 3). However, what South African Gothic suggests (among other things) is that to read for excessively fearful gothic forms in late- and post-apartheid fictions is, in a sense, to engage precisely with states of realness. Gothic figures of unease encode collective anxieties; they possess an experiential truth, which – to borrow Neil Lazarus’s formulation – encapsulates a sense of ‘what it feels like to live on a given ground’ (2011: 133). And as gothic fictions flesh out and give form to these specifically anxious feelings in the contemporary South African context, they also complicate a too-easy rainbowism, which, acquiring hegemonic status, silences those for whom the post-apartheid present is not lived as new.

Rebecca Duncan is Teaching Assistant in English Studies at Stirling University.

Works Cited

Coetzee, J. M., White Writing: On the Culture of Letters in South Africa (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1988).

Comaroff, Jean and John. L. Comaroff, ‘Occult Economies and the Violence of Abstraction: Notes from the South African Postcolony’, American Ethnologist, 26/2 (1999), 279–303.

Gaylard, Gerald, ‘The Postcolonial Gothic: Time and Death in Southern African Literature’, Journal of Literary Studies, 24/4 (2008), 1–18.

Gordimer, Nadine, ‘Living in the Interregnum’, in S. Clingman (ed.), The Essential Gesture: Writing Politics and Places (London: Jonathan Cape, 1988), pp. 261–84.

Lazarus, Neil, ‘Cosmopolitanism and the Specificity of the Local in World Literature’, The Journal of Commonwealth Literature, 46/1 (2011), 119–37.

Punter, David, The Literature of Terror: A History of Gothic Fictions from 1765 to the Present Day. Volume 1: The Gothic Tradition (1980; London and New York: Longman, 1996).