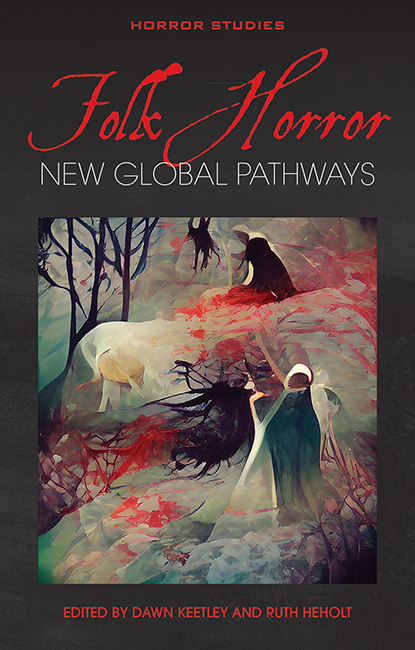

Dawn Keetley introduces Folk Horror: New Global Pathways, an edited volume in our Horror Studies series.

Folk horror’s popularity is not, it seems, going to be waning anytime soon. Director Ric Rawlins, for instance, recently directed a folk horror anthology, Rewilding (2023), steeped in M. R. James’s early twentieth-century fiction and the BBC’s A Ghost Story for Christmas. I’m anxiously awaiting the release of the film adaptation of Andrew Michael Hurley’s excellent 2019 third novel, Starve Acre, about a couple dealing with the mysterious death of their son. The film, according to the production company’s website, follows an archeologist, Richard, who ‘buries himself in exploring a folkloric myth that the ancient oak tree on their land is imbued with phenomenal powers; while his wife Juliette turns to the local community to find some kind of peace, Richard obsessively digs deeper’. Folklore, rural landscape, a powerful nature, multiple kinds of ‘burials’, unearthings and sacrifice are all front and centre in both Rewilding and Starve Acre; all persist as the signatures of folk horror; all seem ubiquitous. Folk horror’s having a moment – and who knows how long that moment will last.

Ruth Heholt and I approached our collection for the University of Wales Press, Folk Horror: New Global Pathways, as academics who love folk horror – and we each wrote about fiction and film we very much enjoy (Ruth wrote about the 1920s fiction of E. F. Benson, set in her home county of Cornwall, and I wrote about films set in the coal-mining regions of Appalachia). The book began with our collaboration on a folk horror conference at Falmouth University in September 2019. It was an extraordinary conference, with some of the most interesting papers and enthusiastic delegates that I’ve ever experienced. Every panel was illuminating, and Ruth and I knew then that we had to publish some of those papers (we could have published more) to get them in front of a broader audience.

We also wanted to expand the borders of folk horror. This post began with two new and upcoming folk horror films that exemplify the British folk horror tradition – and that’s what has also dominated the critical discussion. While both Ruth and I love British folk horror (and have both written about it ourselves), we wanted to bring still more fiction and film into the conversation. Kier-La Janisse’s recent documentary, Woodlands Dark and Days Bewitched: A History of Folklore (2021) does just that, and came out as our book was in its final stages of preparation. We hope our book joins with Janisse’s documentary in widening the discussion about what folk horror is, and where it is.

Folk Horror: Global Pathways certainly includes essays that discuss British folk horror, explicitly taken up from new angles. Chapters explore E. F. Benson as a founding writer (Ruth Heholt), the use of typography in classic folk horror films such as The Blood on Satan’s Claw (1971) and The Wicker Man (1973) (David Devanny), the centrality of the ‘black magic story’ to the genre (Timothy Jones), how the Pendle Witches of Lancashire have been remembered, and politicised, very differently in different historical moments and within diverse regional communities (Catherine Spooner), and the ways in which video games are infused with folk horror iconography (Tanya Krzywinska).

Some chapters look at US folk horror, discerning its lineage in the original Scooby-Doo, Where Are You! (1969-71) (Ian Brodie); two other essays take up the central notion of sacrifice from quite different perspectives, one exploring the ‘black box’ of tradition and human sacrifice in Shirley Jackson’s ‘The Lottery’ (1948), Thomas Tryon’s Harvest Home (1973), and Chad Crawford Kinkle’s 2013 film Jug Face (Bernice Murphy) and another (my own) examining films that remove the human from sacrifice and depict pits themselves – synecdoche for the Appalachian coal industry – demanding their own sacrifice.

Still other chapters explore distinctive aspects of folk horror in other national traditions – the nineteenth-century folkloric origins of gothic horror in Ukraine, with an emphasis on Orest Somov’s fascinating (and quite political) 1833 tale ‘The Witches of Kyiv’ (Lana Krys), the enduring tradition of Phi Pop in Thailand (Kasia Ancuta), the ways economic development has shaped Italian folk horror, notably in Pupi Avati’s incredibly provocative 1976 film, The House with the Laughing Windows (Marco Malvestio), and the shifting incarnations of La Llorona in folk horror, all of which mobilise ‘Mexicanness’ for political ends (Valeria Villegas Lindvall).

Each chapter not only offers rich interpretations of particular folk horror narratives from around the globe but also extends the ways in which we think about folk horror – a project launched by Jeff Tolbert’s opening essay, which tackles the foundational notions of ‘folk’ and the ‘folkloresque’. The concepts of landscape, rurality, regionality, nationalism, folklore, sacrifice, witchcraft, paganism, and – of course – horror pervade the collection.

We hope academics studying folk horror and fans who love the genre (and often they are the same!) find this book – and find it illuminating and useful. We put it together with that hope.

You can find Dawn Keetley on Twitter (otherwise known as X) (@DawnKeetley) and on Facebook (Facebook.com/dawn.keetley). Email address: dek7@lehigh.edu.